I am a Major Leaguer

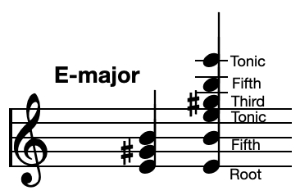

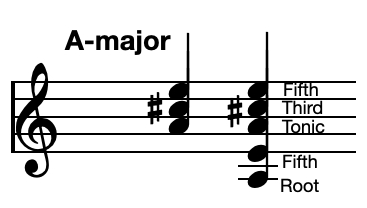

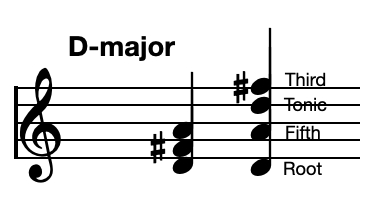

Let's check out the pattern for a major key (2 2 1 2 2 2 1 semitones). It works with any key. We know C. Let's try D major: D E F# G A B C# D. So the key of D would have to have F# and C# to follow the pattern. The key of E is even better: E F# G# A B C# D# E. So the key of E has four sharps. What about F? That would be: F G A Bb C D E F. There's a twist. It turns out that an A# is not convention here. That note is given as Bb instead. Why? Also notice a fifth up from F is C. All the keys that have the sharp right before the octave, will have all sharps. F has the black key A#/Bb in the middle. Also, if we give that name as Bb then a pattern arrises that makes for a very clever diagram.

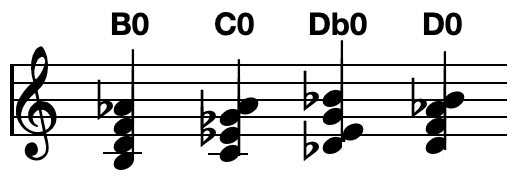

At this point a diagram clears the air. It's called the Circle of Fifths because as you progress clockwise each position is a fifth away from each other. After 12 jumps you're back to the key where you started since there are 12 tones in our music system. But it gets a bit gnarly if you continue using sharps all around. What's cool, if you proceed counter-clockwise an add flats, it balances out nicely at the six-o'clock position.

With C at the top, going clockwise we have G D A E B with progrssively more sharps starting with G with one sharp. The next jump after B lands on F# or Gb. This resolves by going the other way from C and progress through the flats. F Bb Eb Ab Db F#/Gb. So the six o'clock position key is either Gb or F# depending on the composer. But all the keys are a fifth apart an the sharps and flats follow a pattern. This makes it easier to remember which key has what notes in it.

It's a lot easier to see on a piano. What about guitar? We really don't care much when playing chords because the chord patterns set our fingers on the right notes. Patterns become the deciding factor, but to a lead player, you need to know what notes you are playing in any given key. Of course, with all music, your ears are the deciding factor on what sounds good.

One final thing to notice. If you go counter-clockwise around the circle, the notes are exactly a 4th apart - ooh.